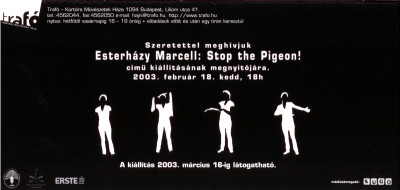

Stop the Pigeon! - exhibition of Marcell Esterházy

Stop the pigeon!

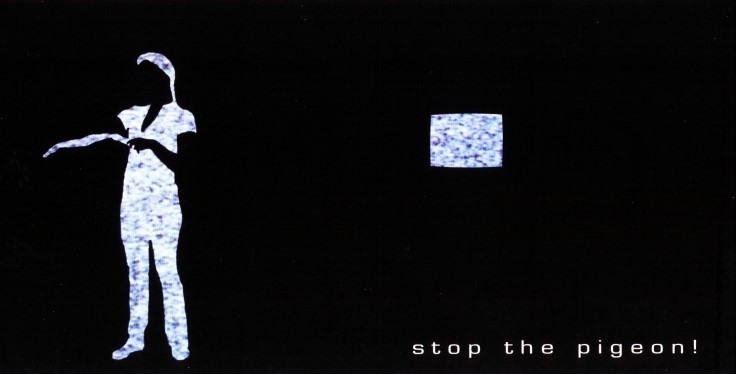

Trafó’s exhibition space plunges in darkness. There is only the vibrating light of video projections contouring the small and simple architectural construction in the middle of space to which the exhibited works, the presentation of Marcell Esterházy’s most recent animations, are reduced. From inside the cube, projected to its four walls, four animations of the series entitled Stop the pigeon! can be seen, the phase pictures of which have been taken by digital camera, manipulated by computer and then put together to a moving picture. I could mention phase pictures because the visual world of videos, the technique and the title chosen for the exhibition carry cartoon references too.

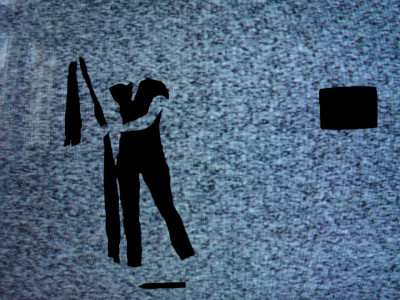

One can “look into” a closed and intimate world through the “windows” cut into the walls, or one can “look out” through them into a city environment seeming usual at first sight. One of the series of scenes, captured using the night shot function of the camera records a series of actions confined to a single room of an apartment, the triviality of which (the heroine reads, sleeps, watches telly or does some work) is only disturbed by the technique itself that was employed. The viewer forced into the position of a voyeur, well known from reality shows, may follow the lonesome activity of a figure wrapping herself in the dark. Only the technology inherited from military technique makes it possible to peep in the hidden hole. Fine irony is smuggled back into the poetic and at the same time baleful pictures by the round silhouette masking known from cartoons, which results from the night shot technique itself. This suggested irony goes over into breezy playfulness in the Magic Pencil story. Recalling the lovely story for children and its unique interpretation tailored to our technical world touches the allegoric dimension of descriptive arts (we can think of the Chinese artist entering his finished tint-drawing or of the Pygmalion story…).

By going all lengths in manipulating pictures in his videos, Esterházy – though in a gentle and talkative style – dissects our perceptional automatisms basically linked to visual representation.

The exhibition borrowed its title from the simple-minded cartoon series shown on an American TV channel that broadcasts only cartoons, the heroes of which are motivated by one thing only: stopping the homing pigeon that should deliver a message which usually, according to the story, no one knows and no one is interested in much. It seems, as if the creator, who experiments with the most varied media and descriptive artistic forms, smuggled back the foundation of McLuhen’s forever valid thesis of “the medium is the message” into the exhibition’s context with the greatest ease and undisguised irony.

The way that led from Marcell Esterházy’s “computer collages” composed of family and other photos that he found or made himself to the animations of the Stop the Pigeon! is almost straightforward. He has been working on a series entitled Originalcopy since 2001. The personages are shown several times in the same collage from various perspectives in the course of the same actions. In his romantic compositions kept close to black-and-white, invoking the atmosphere of old memories, a constantly inquiring attitude is manifested which aims at the quality of photography to document reality.

Found photographs are the starting and inspiring source of his working method already in his early works. In Watery Grave (1998), the photo is stored in a simple laboratory tool, a series of test-tubes. The black-and-white photo taken in the sixties with people splashing about in the swimming pool with artificial waves of the Gellért baths was cut up and closed in the series of test-tubes filled with the water of the baths. The glass capsules plugged with cork stoppers call up the memory of hospitals or research institutes but, within this context, the water sample collection of geologists may also pop up. Small figures with old-fashioned swimming caps on their heads swim in black-and-white, distorted by the water column. Preserved last summer atmosphere closed in test-tubes. Now, there is only a washed out tracery remained from the original shot on the vanishing photographic paper possessed by proliferating must. In the case of Watery Grave, the form implies the intention of conservation, a childish gesture, as if trying to preserve the vanished moment putting it into a preserving agent. Despite the author’s intention, we can witness decay, the complete fade-out of the document.

This work may even be a metaphor of Marcell Esterházy's fluid working method. He experiments with lyric, light and varied media (always using them as tools rather than as the basis of his work), proposing fundamental human issues related to time, transience and remembrance through almost natural associations of objects and ideas.

Mistral, Step-down and Asphalt (2002) are photographs taken by Esterházy himself in Marseille. No manipulation, no computers – just traditional photos. “These are situations as I found them, or plays on the surface”, as the creator writes about them. However, these hard to believe objects and their environment – ownerless shoes stepping down from the pavement, or the motorbike forced into a strange angle by the mistral – suggest setting in, manipulation and composition. But the only thing that operates here is the artist’s sensitive eye that received training from Lucien Hervé’s school. It is the “punctum” theoretically defined by Roland Barthes that exerts its effect on Esterházy’s pictures which may be called classical: details believed neglectable but being all the more captivating, the intensive effect on attention and “story-generation” of pictures picked out of their everyday context.

Esterházy looks around and collects things, and everything catches his eager look while the “matter found” will manifest itself through associations of ideas that are sometimes perplexing sometimes giving food for thought.

He unfolds the possibility of humour hidden in the pictures sometimes through the simplest, almost obvious interventions, such as in the installations Kresz Test Ladies (1999) or Balatoilette (2000). Kresz Test Ladies, with its play on words offering a number of interpretation (KRESZ being the name of the traffic code and “test” meaning body in Hungarian) is based on a found photo, on which the author is not interested in the graceful ladies’ legs showing from under the flapping skirts, but their shadows. The photo that aimed at arresting reality and the moment is reduced to a pictogram by the insertion a simple red triangle: mother with child in black-and-white, well known from the traffic sign warning for the presence of pedestrians. If you neglect the sign, there will be a crash, and the walking ladies will become “crash-test” (see “test” in Hungarian and in English).

Apart from the question of photographic documentation and Marcell Esterházy’s obsession for humour blending with everyday life, he is also known for works where he offers an active role to viewers and involves them in a certain situation. His Gossip-machine (2000) appeared in Trafó’s cafe, outside the exhibition space, so we can say in the real environment of gossiping. The playful visitor had to climb onto a platform to access one of the two parabolic antennas – the “machines” decorated by enormous ears – installed at two opposite corners of the room well above head-height, where he received a laconic instruction in the form of a small pictogram. The Gossip-machine was based on a simple physical phenomenon. The words whispered into the antenna reached the target person standing at the other parabolic antenna without the milling, pleasure-seeking crowd underneath hearing anything. Gossip hangs over our heads, it literally flashes behind us, but at the same time it becomes open and charge is taken for it – preventing it from existing as real gossip – because its author and forwarder appears in public risen above the environment (also literally).

Because it puts the viewer in a special situation, and because of its dialogue generating effect, the Gossip-machine may be paralleled mostly with The creator as server and the receiver as striker (2002). It is when trying to interpret this installation that the most crucial question of what the creative work is may be raised. The digital animation presented in the form of an installation – made with the same technique as the Stop the Pigeon! – followed after a lengthy preparation and research work. The curator had inquired by a questionnaire among visitors about what kind of works of art they would welcome. Some of the people said they preferred an artwork that had something to do with sports. The question and starting a dialogue like this in itself is a provocative approach to the question of artistic autonomy and the problem of “art as a service” that has been demolished by the avant-garde. The objective of the situation generating the dialogue is to create another situation. Esterházy went out for squash with one of the people who gave an answer, he documented the play and finally it was exhibited on the show. The work in this case is not the document but the play itself, the creation of a special situation. From the nineties, the role of the viewer in art shifted from the passive visitor toward being an interlocutor or a partner. The artists, in this sense, do not necessarily create classical object-based works of art any longer. As Nicholas Bourriaud writes [1] "Art, likewise, is not trying to represent utopias, but build concrete spaces [...] It is also an open, indeterminate stage - a platform of propositions [...] But present-day art is also striving to produce situation of exchange, and relational space-times [...] It does not reproduce the world that it has been taught. It tries to invent new worlds, taking human relations as its material."[1]

Edit Molnár

Fordítás: Boros László

Trafó’s exhibition space plunges in darkness. There is only the vibrating light of video projections contouring the small and simple architectural construction in the middle of space to which the exhibited works, the presentation of Marcell Esterházy’s most recent animations, are reduced. From inside the cube, projected to its four walls, four animations of the series entitled Stop the pigeon! can be seen, the phase pictures of which have been taken by digital camera, manipulated by computer and then put together to a moving picture. I could mention phase pictures because the visual world of videos, the technique and the title chosen for the exhibition carry cartoon references too.

One can “look into” a closed and intimate world through the “windows” cut into the walls, or one can “look out” through them into a city environment seeming usual at first sight. One of the series of scenes, captured using the night shot function of the camera records a series of actions confined to a single room of an apartment, the triviality of which (the heroine reads, sleeps, watches telly or does some work) is only disturbed by the technique itself that was employed. The viewer forced into the position of a voyeur, well known from reality shows, may follow the lonesome activity of a figure wrapping herself in the dark. Only the technology inherited from military technique makes it possible to peep in the hidden hole. Fine irony is smuggled back into the poetic and at the same time baleful pictures by the round silhouette masking known from cartoons, which results from the night shot technique itself. This suggested irony goes over into breezy playfulness in the Magic Pencil story. Recalling the lovely story for children and its unique interpretation tailored to our technical world touches the allegoric dimension of descriptive arts (we can think of the Chinese artist entering his finished tint-drawing or of the Pygmalion story…).

By going all lengths in manipulating pictures in his videos, Esterházy – though in a gentle and talkative style – dissects our perceptional automatisms basically linked to visual representation.

The exhibition borrowed its title from the simple-minded cartoon series shown on an American TV channel that broadcasts only cartoons, the heroes of which are motivated by one thing only: stopping the homing pigeon that should deliver a message which usually, according to the story, no one knows and no one is interested in much. It seems, as if the creator, who experiments with the most varied media and descriptive artistic forms, smuggled back the foundation of McLuhen’s forever valid thesis of “the medium is the message” into the exhibition’s context with the greatest ease and undisguised irony.

The way that led from Marcell Esterházy’s “computer collages” composed of family and other photos that he found or made himself to the animations of the Stop the Pigeon! is almost straightforward. He has been working on a series entitled Originalcopy since 2001. The personages are shown several times in the same collage from various perspectives in the course of the same actions. In his romantic compositions kept close to black-and-white, invoking the atmosphere of old memories, a constantly inquiring attitude is manifested which aims at the quality of photography to document reality.

Found photographs are the starting and inspiring source of his working method already in his early works. In Watery Grave (1998), the photo is stored in a simple laboratory tool, a series of test-tubes. The black-and-white photo taken in the sixties with people splashing about in the swimming pool with artificial waves of the Gellért baths was cut up and closed in the series of test-tubes filled with the water of the baths. The glass capsules plugged with cork stoppers call up the memory of hospitals or research institutes but, within this context, the water sample collection of geologists may also pop up. Small figures with old-fashioned swimming caps on their heads swim in black-and-white, distorted by the water column. Preserved last summer atmosphere closed in test-tubes. Now, there is only a washed out tracery remained from the original shot on the vanishing photographic paper possessed by proliferating must. In the case of Watery Grave, the form implies the intention of conservation, a childish gesture, as if trying to preserve the vanished moment putting it into a preserving agent. Despite the author’s intention, we can witness decay, the complete fade-out of the document.

This work may even be a metaphor of Marcell Esterházy's fluid working method. He experiments with lyric, light and varied media (always using them as tools rather than as the basis of his work), proposing fundamental human issues related to time, transience and remembrance through almost natural associations of objects and ideas.

Mistral, Step-down and Asphalt (2002) are photographs taken by Esterházy himself in Marseille. No manipulation, no computers – just traditional photos. “These are situations as I found them, or plays on the surface”, as the creator writes about them. However, these hard to believe objects and their environment – ownerless shoes stepping down from the pavement, or the motorbike forced into a strange angle by the mistral – suggest setting in, manipulation and composition. But the only thing that operates here is the artist’s sensitive eye that received training from Lucien Hervé’s school. It is the “punctum” theoretically defined by Roland Barthes that exerts its effect on Esterházy’s pictures which may be called classical: details believed neglectable but being all the more captivating, the intensive effect on attention and “story-generation” of pictures picked out of their everyday context.

Esterházy looks around and collects things, and everything catches his eager look while the “matter found” will manifest itself through associations of ideas that are sometimes perplexing sometimes giving food for thought.

He unfolds the possibility of humour hidden in the pictures sometimes through the simplest, almost obvious interventions, such as in the installations Kresz Test Ladies (1999) or Balatoilette (2000). Kresz Test Ladies, with its play on words offering a number of interpretation (KRESZ being the name of the traffic code and “test” meaning body in Hungarian) is based on a found photo, on which the author is not interested in the graceful ladies’ legs showing from under the flapping skirts, but their shadows. The photo that aimed at arresting reality and the moment is reduced to a pictogram by the insertion a simple red triangle: mother with child in black-and-white, well known from the traffic sign warning for the presence of pedestrians. If you neglect the sign, there will be a crash, and the walking ladies will become “crash-test” (see “test” in Hungarian and in English).

Apart from the question of photographic documentation and Marcell Esterházy’s obsession for humour blending with everyday life, he is also known for works where he offers an active role to viewers and involves them in a certain situation. His Gossip-machine (2000) appeared in Trafó’s cafe, outside the exhibition space, so we can say in the real environment of gossiping. The playful visitor had to climb onto a platform to access one of the two parabolic antennas – the “machines” decorated by enormous ears – installed at two opposite corners of the room well above head-height, where he received a laconic instruction in the form of a small pictogram. The Gossip-machine was based on a simple physical phenomenon. The words whispered into the antenna reached the target person standing at the other parabolic antenna without the milling, pleasure-seeking crowd underneath hearing anything. Gossip hangs over our heads, it literally flashes behind us, but at the same time it becomes open and charge is taken for it – preventing it from existing as real gossip – because its author and forwarder appears in public risen above the environment (also literally).

Because it puts the viewer in a special situation, and because of its dialogue generating effect, the Gossip-machine may be paralleled mostly with The creator as server and the receiver as striker (2002). It is when trying to interpret this installation that the most crucial question of what the creative work is may be raised. The digital animation presented in the form of an installation – made with the same technique as the Stop the Pigeon! – followed after a lengthy preparation and research work. The curator had inquired by a questionnaire among visitors about what kind of works of art they would welcome. Some of the people said they preferred an artwork that had something to do with sports. The question and starting a dialogue like this in itself is a provocative approach to the question of artistic autonomy and the problem of “art as a service” that has been demolished by the avant-garde. The objective of the situation generating the dialogue is to create another situation. Esterházy went out for squash with one of the people who gave an answer, he documented the play and finally it was exhibited on the show. The work in this case is not the document but the play itself, the creation of a special situation. From the nineties, the role of the viewer in art shifted from the passive visitor toward being an interlocutor or a partner. The artists, in this sense, do not necessarily create classical object-based works of art any longer. As Nicholas Bourriaud writes [1] "Art, likewise, is not trying to represent utopias, but build concrete spaces [...] It is also an open, indeterminate stage - a platform of propositions [...] But present-day art is also striving to produce situation of exchange, and relational space-times [...] It does not reproduce the world that it has been taught. It tries to invent new worlds, taking human relations as its material."[1]

Edit Molnár

Fordítás: Boros László

[1] Nicolas Bourriaud: An introduction to Relational Aesthetics, in: Traffic catalogue, Capcmusée D’Art Contemporain, 1996.