"It's a bitter pill not everyone can swallow" - a conversation with the creators of Blue Lagoon

Dorka Farkas in conversaton with Tamás Ördög, Dániel György Brezovszky, Zsombor Kövesi, Bence Mezei and Daniel Pásztor about directing, nudity and violence on stage, and the role of the audience in theatre.

Trafó. What is the significance of overstepping boundaries in your work?

Tamás Ördög: With every performance, I'm excited to do something that hasn't been done before, to innovate, to go further. What I like in the theatre is when something happens to me. There are very few performances that move me or that are contemporary in a good way meaning that they say something about today for today's people. Here I was interested in how this Blue Lagoon idyll can be ruined. What if this island is not so idyllic after all? What if it isn’t a beautiful boy and a girl who come to this island and fall in love? What if the equation isn't so ideal in the first place?

Trafó: What was your personal motivation for making this performance? What was the idea or need that led you to create this project?

ÖT: I feel that at the moment the theatre is focused on serving the needs of the audience, and this is bad for the creative side. I associate this change or disruption mostly with Covid and streaming services. The viewer is in a very privileged position: billions are invested to satisfy them, to keep them tuned in... And this is the death of theatre. With the Blue Lagoon, I wanted to go against this strategy of instant gratification, so that the spectator could be placed in some kind of a time vacuum - whether they give themselves the opportunity to really get into it is another question. Because unlike Netlfix, this takes work.

Another thing on my mind was whether in 2023 we can even make sense of something that doesn't have a clearly readable story.

Trafó: Yes, in the performance we see situations and recurring tensions. Can we talk about pre-recorded scenes in this performance?

Bence Mezei: We work with panels. This means that there are fixed points that we try to reach in certain parts of the performance to keep the plot rolling. We want to get from one situation to another, but the path itself is built up from the characters, their clashes and collisions. We are actually directing from within - at least that's how I understand it.

Dániel Pásztor: There are some things we have to do at the beginning to get things in order to build up a hierarchy between the four of us. Then new doors can open. It's up to us what we do and how we take in that room, but from there we have to move on to the next door, which opens into another room.

Zsombor Kövesi: In rehearsals it has already happened that a completely coherent story with a conventional arc has been built. But this should never be fixed, because as soon as we start repeating something, it all becomes empty.

Dániel Brezovszky: It always surprises that give you some extra energy.

ÖT: I don't like to direct in the classical sense. I prefer to create frames, structures: a terrarium that we furnish and light together and then put everyone in it. I'm interested in how the people I invite into the project can function in it. This is true for all my performances.

Trafó: One of the central elements of the performance is nudity. How did this come about?

ÖT: Using the Blue Lagoon as a source of inspiration, I felt that there was no getting away from nudity as an issue. I made it clear in the beginning to everyone that this is why I’m interested in now. One of the main elements of being close to nature is not wearing clothes, revealing yourself, your body. Usually we associate sex with nudity, but the special thing about this performance - in the aspect of nudity - is that it is not about sexuality. We were interested in how to achieve intimacy between men without any sexuality. This is a huge taboo.

Trafó: What were your experiences with nudity and how did you prepare for it? What does an intim coach do?

KZs: We go through boundaries and beyond, so that when we're on stage, it's very comfortable. What you see on stage has to be completely casual. Let me give you an example. Or should I not? (looks at Tomi)

ÖT: You may…

(they laugh)

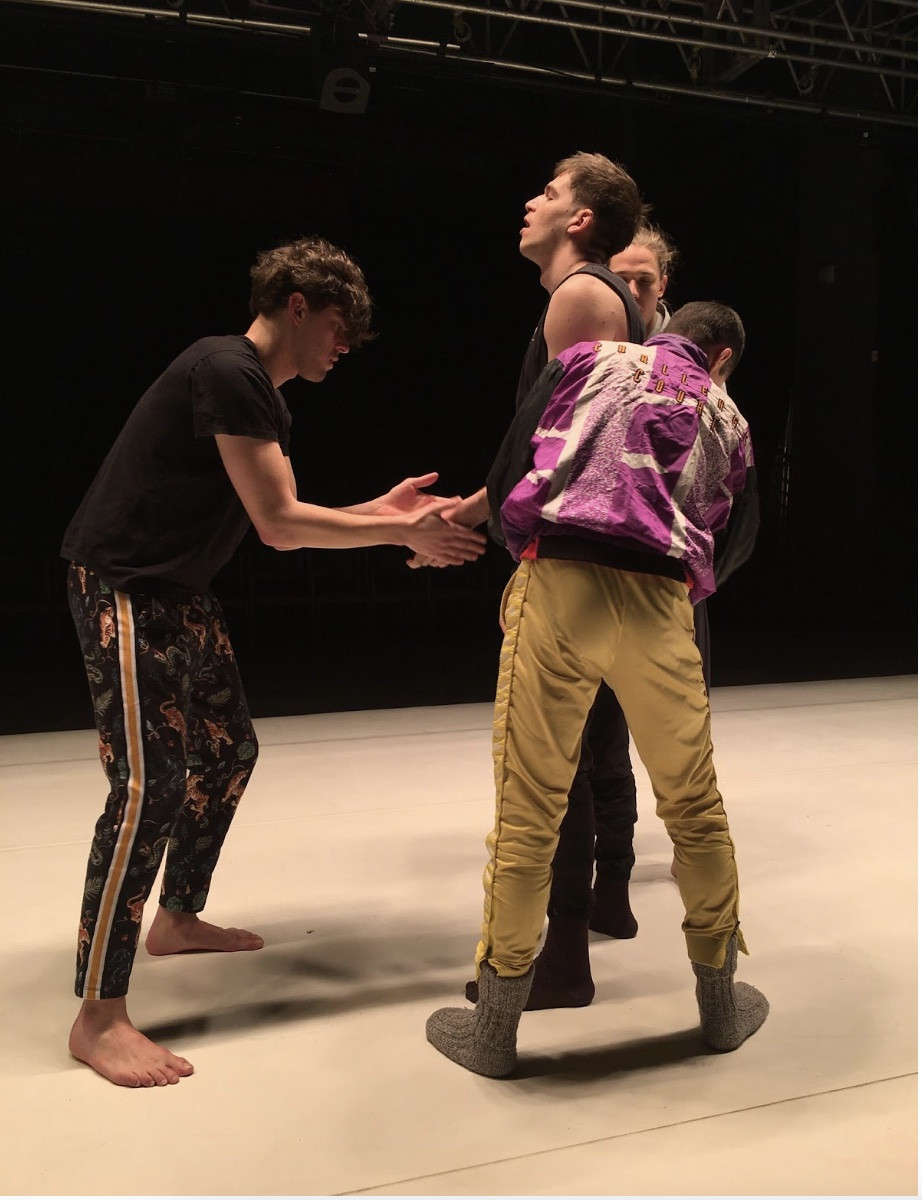

KZs: We were dancing bachata. We were dancing bachata, which I think is much more uncomfortable for men to do with each other than acting like monkeys. [Bachata is a Central American social dance known for its sensual and seductive quality.]

In the picture, Zsombor and Dániel are dancing bachata, led by Adrienn Hód.

BD: It was structured so that there were no shocks. You could feel you were pushing your limits, but we always talked about it or sleep on it. You felt there was a healthy process of overstepping boundaries. And after a naked bachata, it was actually pretty liberating to play as monkeys naked.

MB: We started out in small steps, and by the end we were running in leaps and bounds. For me, by the way, it was endlessly exciting that four men could be together like this, today. As straight men, it’s very hard to achieve, even in our profession, to be in such a relationship with your colleagues.

PD: Well, I can definitely say that I've never been in such an intimate relationship with any partner as I have with these guys. We had some kind of plastic attention to each other because that's what it took to get to know each other's bodies. Like what kind of muscle it is and how it works. Like this you first see a piece of flesh, and only then will you start associating a person with it, and realise that this body is his.

KZs: It must be a shock to the viewer at first glance, because they weren’t moving at our pace. At the beginning I couldn't imagine the state we had reached at the end, but by the end of the rehearsal period, I couldn’t imagine being the person I was at the beginning of the process.

ÖT: It was a long and very intense process. A training. We met every day, did a round of monkeying, talked a lot, always ate together - like monks. I feel that for all four boys it was a big research about themselves. It was important for each one of them to do it at their own pace and go as far as they could go. Hód Adrienn gave a five-day workshop and helped them on this journey by constantly creating opportunities and pushing their boundaries, which helped them to develop and feel liberated.

Trafó: Besides nudity, physical violence is another notable element. Where can the line be drawn between violence on stage and real aggression?

PD: I think it is absolutely separable. I felt safe every time we did it. I never thought that I would actually get hit or grabbed in a way that would result in injury. There was never any real danger, I don't think.

KZs: But there is something about the atmosphere that is created between us and the audience. I've never felt like this with any performance. I could feel that the audience is not thinking about what they're going to have for dinner or what their kids are doing at home, not for a moment. They are present.

BD: There was constant feedback about when someone’s pain threshold was reached. It happened to me once that it flipped into real aggression, but it was a good lesson in how to deal with it. If you feel like you're holding the other person in a way that causes them real pain, that's not okay. You have to be professional at this. I tend to underestimate myself a lot, and it was actually the feedback from the boys that made me realise that I have a lot more strength than I imagine myself to have.

ÖT: Besides nudity, this was the main research: where the line is drawn between the actor’s and the layman’s nervous system. Everyone had to experience that for themselves. Again I must mention this method of monks, the constant doing of it - that gave us a lot of answers. Everybody had to experience extremes, because you can't practice that kind of thing just in your head.

MB: It was trial and error, but with a lot of attention. I think there's definitely a certain degree of masochism in all of this, in the profession itself - both mentally and physically. I think people who do it are looking for a space somewhere where they can experience things that they can't necessarily experience in their everyday life. I certainly have that in me: I can be fulfilled on stage in a way that I can't be fulfilled anywhere else in my life.

Trafó: What can a director do to make sure that such an intense rehearsal process and performance is not mentally taxing?

ÖT: I think a different take on that. I think it has to be mentally taxing, because if it's not, then nothing happens. I think it's a director's job to be able to manage that and to create a safe space for communication, for being together.

Trafo: How do you create that safety?

ÖT: I strive to be an equal partner. I'm not a big believer in this superiority-inferiority thing, but at the same time theatre is not a democracy. I think some kind of a middle ground is good. We do it together, but in the end it's the director's responsibility and duty to make certain decisions. And part of being an intelligent actor is the ability to let go at some point. One ask for last minute changes right before the premier. On the other hand, it's my responsibility to create an environment where the actors can accept that they are safe. It's very important that we can talk things through if anyone has any problems.

MB: You could compare it to a parent-child relationship, or at least that's how I see it. We start together, we go back and forth, and at the end both parties need to have their positions clearly mapped out so that everyone can deal with what they need to deal with.

Trafó: What do you think it says about a performance that the much of the audience walks out?

MB: There are directors for whom this is praise and others for whom it is a failure. I think it's definitely a good situation to have them walk out. I'm not saying you have to lose 90% of the audience, but I think as long as it's half house and we started with a full house, we're totally fine. It also kind of becomes part of the show that there will be people who quit and people who stay. This makes the residual audience connect with each other in a different way. Because something happened.

Trafo: The audience is sitting on both sides of the stage, so they can see not only you, but each other. What is this performance really? Is it circus? A laboratory? Is it for the audience at all?

ÖT: Absolutely, but it wasn't about handing them a delicious cake on a silver tray that we know they'll love. It was more to engage them. In that sense it's a circus because we're giving them an opportunity to get involved. What excites me about watching each other is whether the other side can act as a mirror. You see these creatures, but also see a crowd behind them. The question is whether you have the courage or the nerve to put the two layers on top of each other. It takes courage and effort - of course we can’t know what state of mind people arrive in on that specific night. It's a bitter pill not everyone can swallow.

Trafo: Would you recommend this performance to anyone?

KZs: To my mother.

ÖT: I was going to say the same thing.

(all laugh)