Radical Solidarity

Artist talk: 5pm 26 January, 2008

Interview with the artist

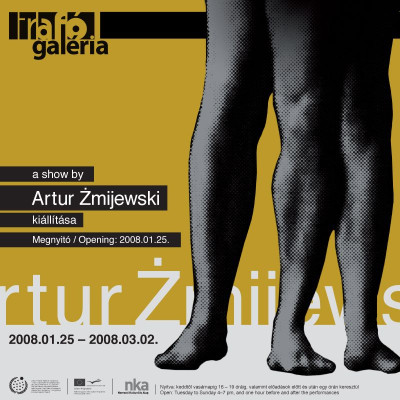

Artur Zmijewski’s figure is as much contradictory as acclaimed in the international contemporary art scene. His films divide the audience: his fans and critics often praise or denounce his works along the lines of similar reasons. Besides having participated at prominent international shows, he was representative of Poland at the 2005 Venice Biennial, and last year he was guest at “documenta 12” in Kassel, one of the most significant events of the contemporary art scene. He regularly publishes articles on the social responsibility of art and raises his voice in public and political debates.

The fundamental experience of his works is how we are constricted by stereotypes and determined by the physical and the social body. The works, however, actually give rise to a completely different situation: the agitated spectator is denied the comfort of pronouncing the artist responsible and dismissing the problem as the private matter of art. The elevating, grievous, or irritating situations represented in the films all culminate in the suspension of the social contracts recognized by most of us. We suddenly glimpse things that have been right before our eyes, unperceived on account of self-defence, weakness of will, or tact; we notice the ‘différances’ scraping the smooth surface of normality. Even if his films are provocative, this provocation is directed not at the characters, but at the moralizing interpretations that tend to circumvent reality.

His working method is consistent: most of the time he creates a basic situation that involves some conflict or fatefulness, and then invites his characters who at once actively influence and passively experience it; the artist, then, retreats behind his camera to follow the events as an observer. Seeing his films, this strategy appears no more efficient than ambivalent. He offers extreme close-up glimpses, bleakly, without any trace of sentimentality. In his case, however, it is not the tradition of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty that comes into play; much rather the tension arising between the identities of the characters and the public thought about these identities.

The proposal he makes in the film An Eye for an Eye tells a lot about living with some aid – about the vulnerability and dependence of both helper and those in need of help. The film features healthy people who lend some of their body parts to those in need of them, serving as instruments in actions no less impracticable than ordinary, merely offering a gleam of completeness. Nevertheless, the series of images, at once hopeless and mirthful, tell us not about redemption, but rather about its impossibility – about finality. This work provides his most tangible expression of the idea of radical solidarity, providing a concept useful in interpreting his later works.

The Singing Lesson 1 presents a similarly absurd enterprise, featuring a group of deaf and dumb youth singing Jan Maklakiewicz’s Kyrie at a church in Warsaw, led by a real choir master. The film forces us to reconcile the excruciating result with the apparent keenness of the singers, testing our tolerance as well as our sense of humour. Although it is expectable from the beginning that the idea of a democratic access to high culture will fail here, the result is not only moving and almost sublime, but it is shamelessly funny.

Zmijewski shot his film Our Songbook at a care home for the elderly in Israel. The characters were elderly Polish people who had emigrated decades ago. The artist asked them to sing the songs they still remember from Poland. The task was not only difficult because of the amount of time elapsed, but also because it involved a return to their roots, which they had been forced to give up. Paradoxically yet not surprisingly, it was the Polish national anthem that their minds most securely safeguarded – the traumas they suffered left it mostly unharmed. Fragments excavated from the abyss of memory relentlessly extricate other fragments, exposing the ambivalent relation of many of these people to their former homelands; exposing the fragility of their hard-won identities.

The film 80064 is centred around the role of victim, the identity-forming power of trauma and around facing the trauma. 92 years old Jozef Tarnawa, former prisoner in Auschwitz, has a clearly visible number tattooed on his forearm, his tag to which he relates intimately: it is an indelible evidence of his personal Holocaust-drama, the cornerstone of his identity. Zmijewski persuades him to let the slightly smeared number be re-tattooed. The old man, who, in order to survive, accepted the conditions of the concentration camp as fateful, now submits to the proposal with resignation, only worrying about the authenticity of the tattoo. However, the relieving force of reliving the trauma – which could easily legitimate the artist and dispel accusations of ruthlessness – quickly expires: victims have no opportunity to forget; they are destined to remember.

In KR WP (abbreviation of the Polish national army’s guard of honour) the uniform corps(e) in service of the nation is literally stripped bare, serving as an ironic criticism of authoritarian control. The uniformed soldiers marching and singing at command, incorporators of the state’s order of battle, are, as one might expect, simple men, who are surprisingly led back into possession of their own body by shedding their uniforms – at a quite comic director’s ‘command’, probably perplexing and embarrassing them a lot.

In his latest work, Them, Zmijewski explores the meagre and distortive nature of radical ideologies through the metaphor of the authority of the image and the authority behind the image, in addition to once again casting light on the ideological neutrality of aggression. The artist invited four Polish activist groups representing four different political views, to visually render, that is, draw, their fundamental ideas. The situation, which began as a creative self-expression exercise, turns into a small-scale clash of ideas and devotions, where ideological differences gradually mingle, and the parties end up expressing their inherent intolerance in frighteningly similar ways. The film presents a social microcosm representative of present times, which, to top it all off, consumes itself through art.

landofhumanrights

Interview with the artist

Artur Zmijewski’s figure is as much contradictory as acclaimed in the international contemporary art scene. His films divide the audience: his fans and critics often praise or denounce his works along the lines of similar reasons. Besides having participated at prominent international shows, he was representative of Poland at the 2005 Venice Biennial, and last year he was guest at “documenta 12” in Kassel, one of the most significant events of the contemporary art scene. He regularly publishes articles on the social responsibility of art and raises his voice in public and political debates.

The fundamental experience of his works is how we are constricted by stereotypes and determined by the physical and the social body. The works, however, actually give rise to a completely different situation: the agitated spectator is denied the comfort of pronouncing the artist responsible and dismissing the problem as the private matter of art. The elevating, grievous, or irritating situations represented in the films all culminate in the suspension of the social contracts recognized by most of us. We suddenly glimpse things that have been right before our eyes, unperceived on account of self-defence, weakness of will, or tact; we notice the ‘différances’ scraping the smooth surface of normality. Even if his films are provocative, this provocation is directed not at the characters, but at the moralizing interpretations that tend to circumvent reality.

His working method is consistent: most of the time he creates a basic situation that involves some conflict or fatefulness, and then invites his characters who at once actively influence and passively experience it; the artist, then, retreats behind his camera to follow the events as an observer. Seeing his films, this strategy appears no more efficient than ambivalent. He offers extreme close-up glimpses, bleakly, without any trace of sentimentality. In his case, however, it is not the tradition of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty that comes into play; much rather the tension arising between the identities of the characters and the public thought about these identities.

The proposal he makes in the film An Eye for an Eye tells a lot about living with some aid – about the vulnerability and dependence of both helper and those in need of help. The film features healthy people who lend some of their body parts to those in need of them, serving as instruments in actions no less impracticable than ordinary, merely offering a gleam of completeness. Nevertheless, the series of images, at once hopeless and mirthful, tell us not about redemption, but rather about its impossibility – about finality. This work provides his most tangible expression of the idea of radical solidarity, providing a concept useful in interpreting his later works.

The Singing Lesson 1 presents a similarly absurd enterprise, featuring a group of deaf and dumb youth singing Jan Maklakiewicz’s Kyrie at a church in Warsaw, led by a real choir master. The film forces us to reconcile the excruciating result with the apparent keenness of the singers, testing our tolerance as well as our sense of humour. Although it is expectable from the beginning that the idea of a democratic access to high culture will fail here, the result is not only moving and almost sublime, but it is shamelessly funny.

Zmijewski shot his film Our Songbook at a care home for the elderly in Israel. The characters were elderly Polish people who had emigrated decades ago. The artist asked them to sing the songs they still remember from Poland. The task was not only difficult because of the amount of time elapsed, but also because it involved a return to their roots, which they had been forced to give up. Paradoxically yet not surprisingly, it was the Polish national anthem that their minds most securely safeguarded – the traumas they suffered left it mostly unharmed. Fragments excavated from the abyss of memory relentlessly extricate other fragments, exposing the ambivalent relation of many of these people to their former homelands; exposing the fragility of their hard-won identities.

The film 80064 is centred around the role of victim, the identity-forming power of trauma and around facing the trauma. 92 years old Jozef Tarnawa, former prisoner in Auschwitz, has a clearly visible number tattooed on his forearm, his tag to which he relates intimately: it is an indelible evidence of his personal Holocaust-drama, the cornerstone of his identity. Zmijewski persuades him to let the slightly smeared number be re-tattooed. The old man, who, in order to survive, accepted the conditions of the concentration camp as fateful, now submits to the proposal with resignation, only worrying about the authenticity of the tattoo. However, the relieving force of reliving the trauma – which could easily legitimate the artist and dispel accusations of ruthlessness – quickly expires: victims have no opportunity to forget; they are destined to remember.

In KR WP (abbreviation of the Polish national army’s guard of honour) the uniform corps(e) in service of the nation is literally stripped bare, serving as an ironic criticism of authoritarian control. The uniformed soldiers marching and singing at command, incorporators of the state’s order of battle, are, as one might expect, simple men, who are surprisingly led back into possession of their own body by shedding their uniforms – at a quite comic director’s ‘command’, probably perplexing and embarrassing them a lot.

In his latest work, Them, Zmijewski explores the meagre and distortive nature of radical ideologies through the metaphor of the authority of the image and the authority behind the image, in addition to once again casting light on the ideological neutrality of aggression. The artist invited four Polish activist groups representing four different political views, to visually render, that is, draw, their fundamental ideas. The situation, which began as a creative self-expression exercise, turns into a small-scale clash of ideas and devotions, where ideological differences gradually mingle, and the parties end up expressing their inherent intolerance in frighteningly similar ways. The film presents a social microcosm representative of present times, which, to top it all off, consumes itself through art.

landofhumanrights